The Vast Eyre Bender: Books

Saturday, December 28th, 2013

Thanks (or apologies?) for the pun to long-time reader and friend VT.

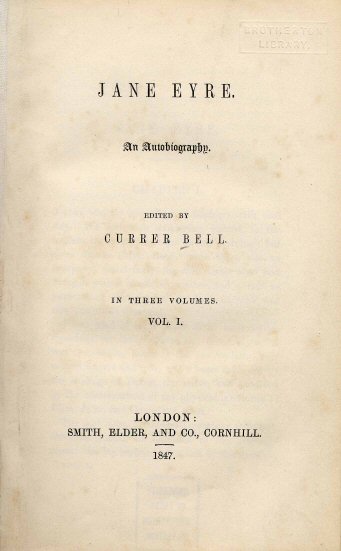

I picked Jane Eyre as the November selection for the book group I lead (as opposed to the two others I just attend.) As the moderator of a discussion of my favorite book, I felt compelled to prepare thoroughly, and spent most of November reading Jane Eyre, related books, and watching all the adaptations. The 20 hours of seven (yes, seven) adaptations deserve their own post, so this one will just be about the ten (yes, ten) books.

Jane Eyre by Charlotte Bronte. One of the first books written in first person from a child’s point of view, with attention to abuse, neglect and poverty. A coming of age, mystery and romance novel that contains one of the most famous metaphors in literature. Jane is a cool customer who speaks truth to power, and carves out her own belief system on the way, one that intriguingly merges Christianity, self-knowledge, and feministic nature.

The Madwoman in the Attic: The Woman Writer and the Nineteenth Century Literary Imagination by Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar. Gilber and Gubar’s chapter on Jane Eyre helped bring that famous metaphor out of the Victorian closet and into wider view.

Wide Sargasso Sea by Jean Rhys. An early intertextual and post-colonial novel that re-imagines the backstory for a character from Jane Eyre. I recommend the Norton annotated edition for its footnotes and essays. The text on its own bewildered me the first time I encountered it.

The Bronte Myth by Lucasta Miller. Excellent detailed history of how the facts and fictions about the Brontes themselves have come to overshadow the genius of their actual works.

The Brontes at Haworth by Ann Dinsdale. Lovely to look at. A good companion to The Bronte Myth.

Down a Dark Hall by Lois Duncan. One of my favorite childhood books, from which I learned that Emily Bronte wrote under the name Ellis and died young.

The Eyre Affair by Jasper Fforde. Hilariously nerdy book about a detective who investigates literary crimes, such as the kidnapping of Jane Eyre.

The Turn of the Screw by Henry James. James’ take on the governess-who-sees-a-ghost tale. The story and premise are great, but I found reading many of the actual sentences tedious.

The Flight of Gemma Hardy by Margot Livesey. A post-WWII update of Jane Eyre set in Scotland. The analog-to-Rochester guy’s secret makes no sense. Not only is it not compelling, but aspects of it contradict one another. Gemma makes an uncharacteristic decision toward the end, there’s an unpleasant hint of homophobia, and the resolution has nowhere near the power of the original. Widely praised by critics, it didn’t work for me.

Cold Comfort Farm by Stella Gibbons. Mentioned in The Bronte Myth and recommended long ago by my friend Becca, I finally got my own copy. Flora Poste is a delight, and I often laughed out loud. Here, she asks about a writer she’s met. The innkeeper tells her:

‘He’s doin’ one now about another young fellow who wrote books, and then his sisters pretended they wrote them and then they all died of consumption, poor young mommets.’

‘Ha! A life of Branwell Bronte,’ thought Flora. “I might have known it.’ There has been increasing discontent among the male intellectuals for some time at the thought that a woman wrote Wuthering Heights.

Cold Comfort Farm was a fun and funny book to end the Eyre Bender with. It has phrases and characters I will never forget.

For the record, reading all these was not only entertaining, but prepared me well for the book discussion.