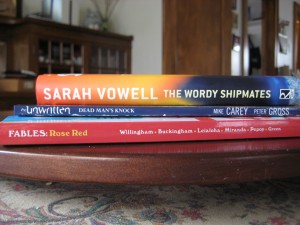

“Riddley Walker” by Russell Hoban

April 22nd, 2011I’ve been reading Russell Hoban’s books since I was a girl, especially the Frances the Badger series, Emmet Otter’s Jug-Band Christmas. I’m reading The Mouse and His Child aloud to my boys right now. When I read The Road last year and again this year, my friend RL said she agreed with a friend who he liked The Road, but admired Riddley Walker even more. Since I’ve been on something of a post-apocalyptic bender lately with The Road and The Handmaid’s Tale, and with Feed, The Hunger Games trilogy and A Canticle for Leibowitz still lingering in my memory, I decided to give it a go. I’m glad I had not one but two recommendations to spur me on. If I hadn’t, I think the challenging language might have stopped, rather than just slowed, me.

On my naming day when I come 12 I gone front spear and kilt a wyld boar he parbly ben the las wyld pi on the Bundel Downs any how there hadnt ben none for a long time before him nor I aint looking to see none agen. He dint make the groun shake nor nothing like that when he come on to my spear he wernt all that big plus he lookit poorly. He done the reqwyrt he ternt and stood and clattert his teef and made his rush and there we were then. Him on 1 end of the spear kicking his life out and me on the other end watching him dy. I said, ‘Your tern now my tern later.’ The other spears gone in then and he wer dead nd the steam coming up off im in the rain and we all yelt, ‘Offert!’ (p. 1)

Riddley is a boy turned man at 12, living in a post-apocalyptic version of England, called Inland, about 3000 years after a nuclear explosion in Cambridge (”Cambry”) put much of England under water and was followed by the usual post-apocalyptic things. Riddley lives in a community called a “fents” in contrast to “forms” in a mostly illiterate iron age. Those who live in a “fents” hunt and gather, while the more stable agricultural “forms” grow more common. Religion and government are combined in The Ram (formerly Ramsgate) and law is spread by itinerant puppeteers who perform morality plays based on the legend of “Eusa” a mashup of the apocryphal legend of St. Eustace with nuclear-scientific history.

I cud feal it in the guts and barrils of me. You try to make your self 1 with some thing or some body but try as you wil the 2ness of every thing is working agenst you all the way. You try to take holt of the 1ness and it comes in 2 in your hans. (p. 149)

Riddley is a sweet, earnest narrator who struggles to figure out what he’s meant for and to do the right thing. The futuristic argot made me slow down as a reader, and Hoban noted that one purpose of the language was to slow down the readers comprehension to the same speed as Riddley’s.

I highly recommend this book for fans of The Road and A Canticle for Leibowitz. It’s challenging to try and parse the language, but as I read it became much clearer, and research I did after helped a great deal, such as this piece in the Guardian, Lowboy author John Wray at NPR, this extensive site of explanation and annotations at Error Bar, and this summary at Ocelot Factory. I suspect Riddley Walker is one I’ll re-read, and that will bring even richer rewards on subsequent readings.