Battle of the Sexes, 1800’s style

Sunday, November 28th, 2010Ah, Tor, thank you. I love me some geekiana.

Ah, Tor, thank you. I love me some geekiana.

Before I begin, I need to ask: Why, oh why, has no one ever recommended Thomas Hardy’s Far from the Madding Crowd to me? But where lame English teachers and even bookish friends may have failed me, perhaps Calliope, the muse of poetry and literature, brought it to my attention.

I recently finished The Hunger Games trilogy, whose heroine is Katniss Everdeen, and Tamara Drewe, a modern re-telling in comics of Hardy’s classic. While reviewing Tamara Drewe, I looked up Far from the Madding Crowd, whose heroine is Bathsheba Everdene. The shared last name of the characters seemed too striking to be coincidence, confirmed in this interview with Suzanne Collins at Entertainment Weekly. Collins states Katniss and Bathsheba are very different, but after reading Hardy, I find a great number of similarities.* But this review is about the Hardy book, so back to it. The book begins with Gabriel Oak, a sheep farmer who’s achieved some small success.

When Farmer Oak smiled, the corners of his mouth spread till they were within an unimportant distance of his ears, his eyes were reduced to chinks, and diverging wrinkles appeared round them, extending upon his countenance like the rays in a rudimentary sketch of the rising sun.

His Christian name was Gabriel, and on working days he was a young man of sound judgment, easy motions, proper dress, and general good character.

When he sees the attractive Bathsheba Everdene, he is struck by her vanity, but soon smitten and proposes marriage. (Bathsheba is named after the married Biblical figure King David, a former shepherd, like Gabriel Oak, becomes smitten on sight with.) Miss Everdene politely but firmly rebuffs Gabriel. Their lives diverge; when they meet again, their circumstances are much changed, though Gabriel’s feelings for the indifferent Bathsheba are not. Through careless and capricious acts, she becomes involved with two more men who desire her: neighboring farmer Mr. Boldwood and handsome soldier Frank Troy. Thus she is part of a love quadrangle, not a triangle like the Biblical Bathsheba is. (King David sent her husband, Uriah, to war, passively but effectively removing his competition.)

Far from the Madding Crowd is a sort of ethnological portrait of the area of English countryside that would become known as Wessex, largely due to its centrality in Hardy’s novels. It’s a character development novel of Bathsheba, an intelligent and complicated female character. It’s also a plot-driven story, intermixing tragic and humorous passages (many of the latter at the expense of women and the rustics, however) on its way to a satisfying, yet subtly complicated ending.

I found Far from the Madding Crowd an involving, provocative book and am glad for the serendipity that led me to it. Though the story was easy to follow, I sometimes felt the prose was difficult. Hardy’s writing is lyrical, but his sentences are often complex, including many instances of parallel, contrasting description and analogy, such as this early passage on Farmer Oak:

when his friends and critics were in tantrums, he was considered rather a bad man; when they were pleased, he was rather a good man; when they were neither, he was a man whose moral colour was a kind of pepper-and-salt mixture.

By the end of his life, Thomas Hardy was known more for his poetry, and had given up writing novels. He was so beloved by the readers of England that they were unwilling to grant his wish to be buried in Wessex. Instead, a gruesome compromise was reached. His heart was removed and buried in Wessex with his first wife, while the ashes of his body were interred in Poet’s Corner of Westminster Abbey.

Far from the Madding Crowd was one of his earliest novels, and his first commercial and critical success. Highly recommended, especially for bookish nerds like me who enjoyed The Hunger Games trilogy. Also, if you are already a fan of Hardy or this book, I encourage you to seek out the graphic novel Tamara Drewe. The recent movie has received middling reviews, but Posy Simmonds’ novel is a treat.

*Similarities of Katniss to Bathsheba. (The characters of Gabriel and Peeta are similar as well: strong, moral, uncomplicated men who adore a woman who values friendship over erotic love.) Both characters are strong women capable of not only surviving but being powerful in a male-dominated society. Both are loved by multiple men, for whom the women have complicated and conflicting feelings. Both would prefer to avoid marriage. In this passage, Bathsheba is likened to the Roman goddess of the hunt, Diana, who is also a model for the arrow-toting, marriage-averse, chaste-minded Katniss:

Although she scarcely knew the divinity’s name, Diana was the godddess whom Bathseba instinctively adored. that she had never, by look, word, or sign, encouraged a man to approach her–that she had felt herself sufficient to herself, and had in the independence of her girlish heart fancied there was a certain degradation in renouncing the simplicityof a maiden existance to become the humbler half of an indifferent matrimonial whole

Near the end of Hardy’s book, Bathsheba collapses and gives way to emotions echoed by Katniss near the end of Collins’ Mockingjay, including the capacity of being cool-headed and capable in moments of crisis, as Katniss is:

Once that she had begun to cry for she hardly knew what, she could not leave off for crowding thoughts she knew too well. She would have given anything in the world to be, as those children were, unconcerned at the meaning of their words, because too innocent to feel the necessity for any such expression. All the impassioned scenes of her brief experience seemed to revive with added emotion at that moment, and those scenes which had been without emotion during enactment had emotion then.

The similarities I found went far beyond the last names of the characters, to their natures, to other characters, and even to the plot. This was a fascinating companion read to the Hunger Games trilogy.

I knew I would read Far Arden sometime, as it’s a lovely looking book by a local author/illustrator of graphic novels. There was nothing to push it to the head of the TBR pile, though, till I was asked to review something for another publication. Then it jumped the queue.

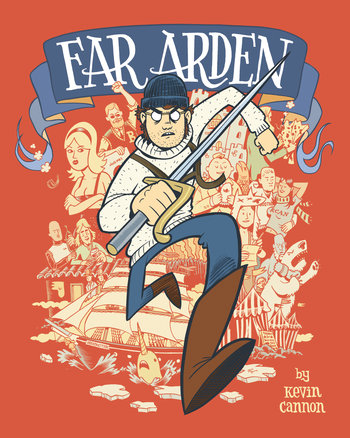

Far Arden cover

Far Arden’s hero, Army Shanks, literally almost leaps off the front cover, surrounded by a lengthy (but not confusing) cast of characters, a complicated past, and a future in which he hopes to find Far Arden, a legendary idyllic island in the Northern Arctic Sea. It starts off as a swashbuckling adventure story: heroes! villains! ex-girlfiends! cute orphans! lost, legendary maps. In spite of many threads and characters, all of this meshes well and swept this reader along at a fast clip, not least because of a clever visual storytelling style and many humorous passages.

In the middle, though, this boys’ adventure becomes something more complicated and interesting. Tragedy intrudes on the characters’ adventures, and a thornier combination of story and emotion takes this in a bittersweet direction to a decidedly noir-ish ending. Fun and funny at the beginning, this goes beyond being a thumping good read. Recommended.

You can check out the whole book online, but if you like it, I recommend buying it. Not only will you support an artist and Top Shelf, one of the rare publisher’s encouraging artist-owned works, but it’s a gem of an object–small, solid, cloth-bound and covered in the colors of sunset and the sea. It feels great in the hand and will be handsome on a shelf. I’ve linked above to amazon, but recommend seeking it out at your local comic shop.

For a fitting explanation of the odd origins of this book, see Kevin’s unique explanation at Powell’s.

At the London Review of Books, Julian Barnes, author of Flaubert’s Parrot and other acclaimed works, on Madame Bovary:

Madame Bovary is many things — a perfect piece of fictional machinery, the pinnacle of realism, the slaughterer of Romanticism, a complex study of failure — but it is also the first great shopping and fucking novel.

He discusses, with several examples, the perils of translations and what strengths the new one by Lydia Davis has, and has not. I’d wait till after you read the Davis translation to read this piece, though. Link from Blog of a Bookslut.

This bookshelf is sad because everyone (except me!) has an e-reader:

As I wrote about recently, I’m trying to start a family movie night tradition. In theory, it’s supposed to be on Friday after pizza, but in practice it’s kind of jumping around a bit and not attached to one particular food yet. But I’ll keep trying.

A few years ago, I tried to watch Mary Poppins with Drake, who was maybe 4 or 5 at the time. He was frightened by the booming cannon at the beginning, and refused to watch again till last weekend. So it was with some hesitation that I popped in the 139-minute movie. But both 7yo Drake and 4yo Guppy were unperturbed, and we went on to watch the first half of the movie, which included the classics “Spoonful of Sugar” and “Supercalifragilisticexpialidicous,” which Drake had a hard time wrapping his mouth around. Funny, how my husband G. Grod and me must have had to practice as children too for it to come so trippingly off our tongues as Drake struggled. We saved the second half for the next night, and it went just as well. The kids were delighted with it. I have been less delighted to find myself with some of the songs stuck in my head this week, but I hope that will pass.

The kids were less delighted when I borrowed John Sayles’ Secret of Roan Inish from the library. They were happy to watch the cute seals, but the long intervals of storytelling and flashback were too much for them. The main character, Fiona, is such a brave, scrappy little girl I think this is a good girl-power movie. But probably for older kids than 7yo Drake.

When I review or recap books and movies, I try to sketch only the broadest strokes, telling little more than what can be determined from the jacket or a movie trailer. I give my reaction, and try to give enough information for the reader to decide for herself whether she’s likely to enjoy it. This approach will be difficult with Suzanne Collins‘ Hunger Games trilogy: The Hunger Games, Catching Fire, and Mockingjay. I don’t want to spoil anything for those who haven’t yet read it, yet I want to give enough information to help those on the fence decide whether to read it.

I’ll begin with the first book, The Hunger Games. It’s a young-adult fantasy novel narrated by a 16 year-old girl whose world is both like and unlike our own:

When I wake up, the other side of the bed is cold. My fingers stretch out, seeking Prim’s warmth but finding only the rough canvas cover of the mattress. She must have had bad dreams and climbed in with our mother. Of course, she did. This is the day of the reaping.

Collins gradually adds detail to the girl’s life and her world until the Hunger Games of the title is explained. Anything more, and I risk giving away one of the strengths of the book, which is the author’s slow and effective construction of the characters, their universe, and the Hunger Games. The main character is likable, her situation sympathetic, and the story filled with action, romance, mystery and danger. There is darkness, death, and murder, though, so this is not for younger children.

The second and third books are similarly engaging and quick to read; I finished all three in less than a week. Book 2, Catching Fire, and book 3, Mockingjay, continue the tale begun in book 1, giving further detail to the world, as well as moving the story forward in often disturbing, though perhaps inevitable, ways. Each book is progressively darker and more violent than the one before. Not only do terrible things happen, but they happen to children. The 2nd and 3rd books go beyond the death and murder of the first to include references to underage prostitution and grim torture.

I don’t want to scare people off; this trilogy is a thumping good read. But the complicated pleasure of a thrilling story comes at the price of a great deal of fictional violence and pain. Once the first one is devoured, I can’t imagine not reading the 2nd and 3rd in short order. Yet the 2nd and especially the 3rd are way more to handle than the 1st. Enter this series with caution, because once begun, you’ll likely be with it to the end. And parents should definitely read this before OKing it for kids, in my opinion.

Interestingly, in spite of copious violence and a few references to prostitution, I found an almost total lack of sexuality in the book. I found this strange, given its teen protagonists, who I assumed would be bundles of hormones. While I can see this being a good thing for parents worried about the over-sexualization of teens in books like the Twilight and Gossip Girl series, the almost surreal chasteness of the characters rang false to me. Over the course of three books, so did some of the characters themselves. In one book this can be excused by the primacy of the story. Over three books, I felt many characterizations were stretched thin rather than fleshed out.

I knew these books would be difficult to write about. There are many passionate and devoted fans of the series, and I fear I’m doing a disservice to the many things that are good about this series by writing my reservations about it. Yet while I’m glad I read it, I’m fairly certain not everyone would be. Like the Harry Potter series, and perhaps even a little more like Stieg Larsson’s Millennium series, The Hunger Games trilogy has a tough, sympathetic survivor of a main character. Over the books, though, bad things happen to her and those she’s close to. These things happen again and again and again. The series won’t work if you’re in a fragile, blue mood or if you have a hard time reading fictional violence in general or against children. If you’re feeling tough, though, and ready to wrestle with some thorny questions of situational morality around government, violence and young people, then go for it. And we can talk about it when you get to the other side.

Spa treatments–lovely, but costly and time consuming. Just not possible, lately. I’ve often attempted to duplicate services at home, with varying results. I do a pretty good mani/pedi. However there was that time I added baking soda to my shampoo, and somehow got ammonia. There was the time I tried a salt scrub, but the salt was too coarse and wouldn’t dissolve and hurt to step on in the shower. Or the time I mixed brown sugar and olive oil to make a body scrub and the shower was so slippery I nearly fell and had to immediately wash it. Or when I tried Sally Hansen’s Airbrush Legs and turned the shower orange and immediately had to wash it.

Upon consideration, my misses outnumber my hits.

In spite of that, I keep trying. Last week’s experiment was a scalp scrub combining brown sugar and heavy cream. It felt great and I was smug, till my hair dried and I wondered what that bad smell was–my hair smelled like soured cream. Then Guppy got sick and barfed everywhere and I had a hard time distinguishing between the smell of barf and the smell of my hair. I tried to wash it out. Once didn’t do it; I think the smell was embedded in my scalp. I did a double shampoo this morning, (normally verboten on the Curly Girl care regimen, but desperate times, and all. Plus, I got the idea for the heavy cream from Curly Girl! Fail! Fail!) and I’m still not convinced it’s gone.

This should put me off any more home spa attempts for a while. Until I forget, and then I’ll be all, “I don’t know if this is a good idea, but I’m going to do it anyway.” Story of my life, I swear.

4yo Guppy had an activity at preschool last week called detective book. The students were to draw or try to write down the things they saw. Guppy has begun to connect reading to writing and spelling, so his book was filled with words. Some were easy to guess: RASCAR for racecar. HORT for heart (they’ve been studying the human body). BATMOBEYL (I don’t need to translate that, right?) FEMER BON for femur bone.

One perplexed both my husband G. Grod and me: COWED. Yes, it’s a word, but not a noun, and not one that made sense in context. At home, we asked him what he meant. He pointed to my computer, and slowly said, “COH-WUD.”

It took me a moment to realize what he meant. The power CORD. We laughed. Then I fretfully wondered: if he’s transcribing his sometimes still mushy speech patterns, perhaps it IS time to see a speech teacher.

Nah. Forget it. I love his mushy Rs.

My friend Big Brain pointed out Tamara Drewe, a graphic novel, to me when I was in the comic shop last week.

I’d heard of the film (which has received mostly mediocre reviews) but he said the GN was well reviewed, which is almost understatement when I looked at the blurbs on the back. They are from reputable sources and aren’t stinting in their praise.

Posy Simmonds is a graphic artist who has done children’s books, this and a previous graphic novel, Gemma Bovery, and more. Tamara Drewe the book is a modern retelling of Thomas Hardy’s Far From the Madding Crowd. The setting is the English countryside, at a retreat for writers. I haven’t read the Hardy, but am now interested in it because of this engaging homage.

Simmonds combines the art, prose passages, faux tabloid excerpts and word bubbles to great effect. This is absolutely a whole that is more than the sum of its parts, in other words, a skilled execution of the medium of the graphic novel, made all the more engaging by its involving story and broad cast of characters.

Tamara of the title tempts all the men when she returns to the neighborhood. She begins a rocky relationship, but continues to attract attention from the men and bored teens in the neighborhood. Other’s stories circle around hers. Beth oversees the writers retreat, while her novelist husband Nicholas earns fame and money to make it popular. One of the residents, Glen, is long at work on his academic novel. Local Andy Cobb is trying to start an organic farm, and helps out on the grounds of the retreat. Two local girls, Casey and Jody, goggle at Tamara and her boyfriend and get into a variety of trouble.

Having recently read two 19th century novels, Villette and Madame Bovary, I found this work very much in the same spirit. Many characters, many characters, with crossovers and coincidences tying everything together in complex and interesting ways. Unlike the other two books, though, it didn’t contain any digs at the Jesuits. It’s beautifully illustrated, and is much more than an illustrated novel. Highly recommended, and I’ll be seeking out both Simmonds’ other work and potentially the Hardy because of it.

One piece of minutiae: Glen Larson is an American, yet used two phrases that didn’t ring true to me. He called his sweaters “knits” at one point, and referred to himself a few times as a “pantyhose.” If the latter is indeed English slang (I thought it was pantywaist, not pantyhose) then both are easily explained as Glen picking up English slang while he’s there. But if were speaking American, he would say sweaters and refer to himself as a douchebag.

Another, and this is me being especially nerdy. The main character’s name reminded me of Nancy Drew, one of the fictional characters for whom I took the name of this weblog. Glen’s last name is Larson, the same as Glen A. Larson, the man who produced the Nancy Drew and Hardy Boys mystery show that was a huge cultural moment of my childhood. A strange coincidence?

A third thing that struck me: the heroine of Hardy’s novel is Bathsheba Everdene. I’m currently reading The Hunger Games, whose main character is Katniss Everdeen. Again, strange coincidence, or just mega-geekery on my part?

It seemed like such a good idea at the time. My friend Amy, who blogs at New Century Reading, told me the writer at Nonsuch Books was doing an October reading of the new Lydia Davis translation of Flaubert’s Madame Bovary. “I’ve always wanted to read that!” I exclaimed, as if this were justification enough to

1. Run out and buy the hardcover. (But I had a coupon! And I bought it from a local, independent bookstore!) (Hush, you.)

2. Put it at the front of my reading queue ahead of other books I’d committed to read for real-life book groups, like John Jodzio’s If You Lived Here You’d Already Be Home, and Villette, the length and challenge of which I severely underestimated.

But, as my epitaph will one day likely read, “it seemed like a good idea at the time.” Or, “I wasn’t sure it was a good idea, but I did it anyway.” And there were consequences. I didn’t finish Villette, which I enjoyed, in time for the book group, so was unable to discuss the significance of the ending. And I felt compelled to finish Madame Bovary, which I did not enjoy, and didn’t get to discuss online, either.

Don’t misunderstand me. When I say I didn’t enjoy it, I don’t mean it wasn’t great, which it was, or that I’m unhappy I read it, which I’m not. It’s one of the classics that is referred to so often that impressions of it form even without reading the referent. I’m glad to have read it myself, and formed my own opinion.

Before I read, I knew only that Madame Bovary was a wife unfaithful to her husband. I suspected he’d be really dull and I’d sympathize with her attempts to burst the bounds of a stifling marriage. I was surprised and impressed to find something much more complicated. In her introduction, translator Lydia Davis notes that, in writing Madame Bovary, Flaubert

set himself a formidable task–to take…grotesqueness as his subject, to write a novel about shallow, unsympathetic people in a dreary setting, some of whom make bad choices and come to a horrific end. ((xiii)

I found this a dead-on description of the book, though it’s hardly back-cover blurb worthy, is it? Instead, Flaubert wanted to tell a tale from life, with all the mundane details and without moralizing. This scandalized people of the time. He aimed to do it so the style of the book would make it readable and important even if the particulars were unpleasant.

Deep in her soul, however, she was waiting for something to happen. Like a sailor in distress, she would gaze out over the solitude of her life with desperate eyes, seeking some white sail in the mists of the far-off horizon. She did not know what this chance event would be, what wind would drive it to her, what shore it would carry her to, whether it was a longboat or a three-decked vessel, loaded with anguish or filled with happiness up to the portholes. But each morning, when she awoke, she hoped it would arrive that day, and she would listen to every sound, spring to her feet, feel surprised that it did not come; then, at sunset, always more sorrowful, she would wish the next day were already there. (53)

It’s the style that stands out. There are long, lovely passages, interrupted deliberately by short, brutish ones. There are characters who are their own worst enemies. There is even a fair amount of dark humor, though the rest is so tragic and pathetic that its leavening effect is negligible. As in Villette, which I read at the same time, the Jesuits came in for a lot of criticism.

I’ve not read other translations, so I can’t speak to the superiority of this one. I can attest, though, that it was eminently readable, and indeed impressed me with its style and eloquence, even as my spirits were damped by the bad behavior and sad circumstances of its characters. I was glad to be done with this novel, but still satisfied to have read a literary touchstone for myself to better understand references to it the next time (and there WILL be a next time) I come across them.

Looking back, I could have waited to get this from the library, and to read it when other books weren’t clamoring for my attention. So I say, as I’ve said before, no more haring off after online book challenges. I’ll keep to my own reading schedule. And make up my own arbitrary challenges.

Edited to add: I’ve continued to think about Mme. Bovary since I read the book, and am ever more glad for having finally read it. Further, I’ve done some related reading and writing since I wrote this.

Review of Flaubert’s Parrot by Julian Barnes

Review of Gemma Bovery by Posy Simmonds

Julian Barnes review of Davis’ translation, “Writer’s Writer and Writer’s Writer’s Writer”

At Boston.com, “Lost in Translation,” an essay on the the “ooh, shiny, pretty!” aspect of new translations

Prior to reading Charlotte Bronte’s Villette, I owned two copies of it. One was an antique-y harcover with black and white photo illustrations. The other was a pretty blue softcover in a slipcover that my husband G. Grod brought home for me one day because he thought I might like it. I certainly did. However, in typical fashion, the possession of both these lovelies did not induce me to immediate reading of said treasures. Like so many do, they languished on the Bronte shelf, gathering dust.

Until last month, when I pulled them off to show to my book group, and we decided to read Villette. And, with all good intentions, I ended up accumulating three more copies.

Alas, the blue volume in the slipcover was deceptively slim. Because of small type and thin pages, it, like most other editions, ran nearly 500 pages. Also, it was not an easy read for me, as I had found Jane Eyre. The text is rife with Biblical, mythical, and literary allusions, many of which I did not know. Embarrassing, since I have a degree in religious studies. However my seven years of French stood me well; I could understand most of the many passages in that language. If you do not speak French, be sure to get an edition that translates the phrases, or you will miss much of the dialogue when the scene shifts to Villette, France, a fictionalized, none-too-kind version of Brussels, Belgium.

I struggle with what to write about the book, because there is an ambiguity many have found at the beginning I don’t want to dispel, yet without which it’s hard to describe the book.

In the autumn of the year ____ I was staying at Bretton; my godmother having come in person to claim me of the kinsfolk with whom was at the time fixed my permanent residence. I believe she then plainly saw events coming, whose very shadow I scarce guessed; yet of which the faint suspicion sufficed to impart unsettled sadness, and made me glad to change scene and society. (Ch. 1 Bretton)

Is the narrator telling her own story, or that of another girl? This eventually becomes clear, and we follow a young woman from Bretton to London to “Villette”. She is tossed about on waves both literal and figurative; questions of fate, love, justice and imagination pervade the book. Taking employ at a school for girls, the young woman adjusts to her new surroundings and is a fierce and sharp observer of others. She is not, however, always a sympathetic character, and the narrator is a decidedly untrustworthy one, as the reader learns, right unto the end. Contrasts, in a character, or between characters and situations, are rife. These can be unsettling and feel jarring, yet made sense to me as I reviewed the book once I was done.

It is often noted that Charlotte Bronte criticised the work of Jane Austen for being passionless and mannered. No one could argue that the main character of Villette doesn’t have surging passions:

once breaking off the points of my scissors by involuntarily sticking them somewhat deep in the worm-eaten board of the table before me. But, at last, it made me so burning hot, and my temples and my heart and my wrist throbbed so fast, and my sleep afterwards was so broken with excitement, that I could sit no longer. (Ch. 13 A Sneeze out of Season)

And she barely disguises the sexuality she struggles to keep in check:

Conceive a dell, deep-hollowed in forest secrecy; it lies in dimness and mist: its turf is dank, its herbage pale and humid. A storm or an axe makes a wide gap amongst the oak-trees,; the breeze sweeps in; the sun looks down; the sad, cold dell, becomes a deep cup of lustre; high summer pours her blue glory and her golden light out of that beauteous sky, which till now the starved hollow never saw. (Ch. 23 Vashti)

Yet reading Villette, I was reminded strongly of two characters from Austen’s work. The narrator reminded me of Fanny Price from Mansfield Park, as she is a frequently judgmental observer of the more worldly characters around her. Further, the character of Ginevre Fanshawe, a vain, pretty girl, reminded me of Lydia from Pride and Prejudice.

This is a big, complicated novel that is nonetheless entertaining, though perhaps in a way less obvious than many find Jane Eyre. I loved Jane Eyre, and found many similarities in this book: cross-dressing, attics, and tyrannical religious types among them. (Jesuits fared especially poorly in Bronte’s estimation. They were repeatedly characterized as sneaky and less than truly charitable.) I found Villette more challenging to read than Jane Eyre, but also, in the end, more rewarding. The work I put into reading slowly, getting a good edition with thorough notes, following up on things that weren’t noted, left me with a deep respect and affection for the book. One benefit of having five editions of the book was five different introductions to read afterwards (of five, only the Oxford edition kindly notes: “Readers who are unfamiliar with the plot may prefer to treat the introduction as an afterword.”) Together, these helped reinforce basic biographical information, yet added insights unique to each edition.

For much more Bronte goodness, visit the Bronte Blog.

I am laid up in bed with a spot of pneumonia in my right lung, diagnosed right after I voted on Tuesday. I’ve been resting since then, since I think it’s the result of a cold/cough that I didn’t rest enough for over last weekend, and which seized the opportunity to invade. Since Tuesday, then, pretty much all I’ve done is read, be on the computer, watch TV, and sleep (or rather, TRY to sleep, since the painful lung makes it as hard to find a comfortable position as advanced pregnancy did), and lie abed. I did take a short walk yesterday, in the balmy afternoon. It left me panting and exhausted.

Unfortunately, my boys have the next 2 days off school for conferences. Fortunately, so does their babysitter, who is here all day so I can stay abed and she can run them outside. Somewhere after 4yo Guppy was born, I learned that resting and self care were not frivolous indulgences, at least for me, but necessary at times to keep going, both in the short and long term. This lesson took me a long time to learn. As I’ve written before about napping, I didn’t think I was capable of it for a long time, till I practiced. Now I’m queen of the 20-minute snooze. Same thing with resting and taking care; it’s a skill that takes practice.

This time, at least, I’m helped by my husband G. Grod, who was able to work from home the past 2 days, and who keeps reminding me that if I don’t rest now, all of us will suffer for it later.

I’ve fortified my sickbed well. I’ve got a warm duvet, Euro pillows for back propping, a yoga bolster for knee propping, a lap desk and my computer. Books, comics and magazines to read, throat drops, lavender spray, books to blog about, notebook, journal, tissue box, water bottle, giant mug of ginger tea with honey and baguette slices with butter. I am dressed warmly in comfortable clothes. I have a scarf wrapped around my head to keep my ears warm. I plan only to leave the sickbed for bathroom breaks and lunch, and possibly a little smackerel of something around 3.

Here’s what I’m not doing: making phone calls, making lunch for the kids, mediating their fights, keeping them to the usual limit of one hour of screen time/day, catching up on insurance paperwork, doing laundry (even though the boys don’t have clean socks–they’re wearing dirty ones), putting away laundry, straightening, puttering, stressing out. I do have the lurking feeling I should be darning socks, or rather learning to darn socks, then doing so. But I’m gently pushing this aside for now. I’m sick; if I don’t rest I’ll likely get sicker. So might as well rest, since I’m fortunate enough to be able to do so. And since I’ve practiced it enough that I’m actually capable of doing so. Sounds quiet downstairs. I think I’ll sneak down and heat up some soup.

I’m trying to start a new tradition in our family, inspired by Claire of Little Farm, Growing: Fridays as Family Pizza and Movie Night. We’re three weekends in, and I have to say, it’s not really a hard sell. For the first week, my husband G. Grod borrowed 9 (the animated film, not the dancing debacle) at 7yo Drake’s request. This didn’t turn out so well. First, I made the pizzas and didn’t get started till late, so I didn’t get to watch. Second, the movie was too scary for the boys. I asked Drake to get some socks from the laundry room the other day.

“You go,” he said. “Memories of 9 keep me from going into darkness.”

He phrased it so poetically; how could I not comply?

The next two weeks worked out much better, with animated films by one of our favorite film makers, Hayao Miyazaki. He has been, incorrectly to my mind, described at the Japanese Walt Disney. A more accurate analogy is that he’s like the Kurosawa of animation. In the U.S., he is perhaps best known for his sweet children’s fable My Neighbor Totoro, or the more recent Ponyo. We chose two of his earlier works, as the later ones, including Princess Mononoke, Spirited Away are too violent, IMO, for small children.

Porco Rosso is the story of a former Italian army sea-plane pilot, Marco, who’s been cursed by a witch to take the form of a pig. He frequents a small island bar reminiscent of that from Casablanca. It’s run by Gina, whose pilot fiancee was shot down in the war. Porco has trouble with sea-plane pirates, as well as an uppity American pilot who is vying for Gina’s affection. Along the way, Porco has to deal with costly repairs, police pursuit, and the company of Fio, a traditional Miyazaki heroine: smart, brave and cute as a button. (No mincing princess, she.) It’s a rousing, romantic tale, and charmed both the parents and kids. I’m thrilled to see a sequel is in pre-production.

Castle in the Sky refers to a floating island, pursed by young Pazu, whose father died soon after seeing it. (In Japanese, the movie was called Laputa, a hat tip to the inspiration from Gulliver’s Travels.) Most people believe it’s a myth, but two others seek it as well: sky-pirate queen Dola, voiced with cackling relish in the US version by Chloris Leachman, and bad-guy secret-agent Muska, voiced by Mark Hamill. Both of them want to kidnap Sheeta, a young girl with an ancient crystal connected with Laputa. But when Muska’s sky ship crashes, Sheeta escapes, and is found floating and unconscious by Pazu who seeks to shield her from her pursuers. This is a suspenseful tale with an undercurrent of the eco-awareness found in other Miyazaki works. There’s adventure, cool robots, treasure and smart, capable kids. As with Porco Rosso, this was a movie that delighted both me and the children.

On deck? We have many movies at home, but I’ve just reserved John Sayle’s Secret of Roan Innish. I saw it years ago at a Philadelphia film festival before it received distribution and was so glad when it did get picked up and released to glowing reviews.