My Neil Gaiman Story

Saturday, April 30th, 2011or, How Neil Gaiman Depedestalized Himself. I find it hard believe I haven’t written this story before. If I have, I can’t find it, so here it is.

Neil Gaiman’s Sandman was one of my gateway comics, way back in 1990. A boyfriend urged it on me along with some of the usuals, like The Dark Knight Returns and Watchmen. But Sandman–with its literary references, magic, horror and mystery–was really what hooked me. I started reading during the Season of Mists story line, which is still one of my favorites. I became a geek girl, devouring old series (Alan Moore’s Swamp Thing and V for Vendetta, Baron and Rude’s Nexus, Morrison’s Animal Man and Doom Patrol), showing up at my comic shop on Wednesdays for new comics, and appreciating the attention I received there as a not unattractive female of the species.

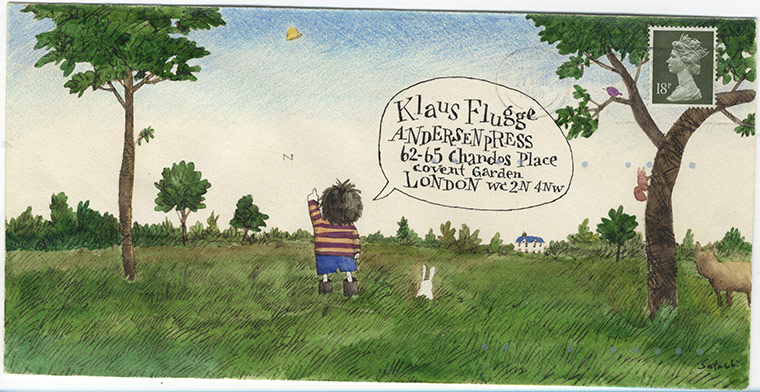

Sometime in the early 90’s, Gaiman scheduled a signing at my then comic shop, Fat Jack’s Comicrypt on 19th Street in Philadelphia. I planned carefully for the event. I picked out my favorite outfit, and selected my three items to have signed. I wanted to convey that I was better than the average fan, so I didn’t want to only take recent stuff. After nerdishly obsessing for far too long, I selected the first graphic novel collection of Sandman, Preludes and Nocturnes; issue 19, “A Midsummer Night’s Dream“, which I liked so much I’d bought the individual issue even though I had it collected in Dream Country; and Black Orchid, an obscure DC universe character he’d resurrected in a beautifully painted story by Dave McKean.

I pondered the questions I would ask him. They had to be things I was really curious about, plus that would display how cool I was. The fantasy scenario in my mind was pretty clear. My cuteness, smart questions and interesting signing picks would single me out of the crowd. Neil (of course I was thinking of him on a first-name basis) would ask me to join him and his team for dinner that night. And the obvious would happen: we would become friends. Interestingly, this was strictly a platonic fantasy. He seemed much too old for me, more like a young uncle than a potential love interest. Anyway, he was married and I had a boyfriend, and it just wasn’t on my mind.

The day arrived; I left work early. I found a parking spot on the street just a few blocks from the store. I loaded the meter with quarters, and prepared to meet my destiny. (Sandman pun not intended.) The line, when I arrived, was nearly out the door. I thought I was lucky to be inside, but soon realized the tradeoff. It was a warm summer day outside, and positively stifling inside. Many in line were not conscientious about personal hygiene. The line moved slowly. The grey cat atop the back issue boxes surveyed us all with disdain. Sweat trickled down my back and from under my arms. My hair expanded to a gigantic frizzy triangle. The books I clutched had damp handprints on them. Gaiman and his assistant took a break near the end of the hour I’d thought would be more than sufficient on my meter, and the time approached for the class I had that night. I was not near the front of the line. I asked the guys in front of and behind me in line if they’d save my space, overcoming a flash of grade-school embarrassment. The guy behind me looked annoyed and merely nodded. I had to wade through the crowd to the register to get more quarters. Once outside, I breathed in the relatively fresh air. If you’ve ever been on a street in summer in downtown Philly, you know the steaming, fug-spewing grates on most corners. Still, it compared favorably to the inside of the comic shop. I ran the blocks to my car, plugged the expired meter, and raced back. The line had barely moved. The guy who’d been behind me glared, and didn’t make room for me in line. I glared back, put my shoulder down, and wedged my way back in. Time passed. Gaiman chatted equably with those at the head of the line. The rest of us shuffled forward. The additional hour on my meter ticked down. My class was about to begin. Finally, oh, finally, I reached the head of the line.

“Let’s take a break, get a sandwich, shall we?” said Gaiman’s assistant.

“No!” I cried, desperate and without shame.

Gaiman, his assistant, and the comic-shop guy looked at me as if I’d sprouted a head.

“Please,” I added in what I hoped was a more reasonable tone of voice. “My meter’s about to expire and I have a class I have to get to. Can you please sign these before your break?” In other words, I begged.

Gaiman shrugged and held out his hands for the books; the assistant rolled her eyes and asked him what he’d like to eat. He scribbled a signature in my book without looking to see what it was. I waited for him to answer her so I could ask my questions.

“Are we going to find out how Delight became Delirium?” I said.

He didn’t look up from the book he was signing. “Someone else is going to do that.”

Daunted but determined, I forged ahead, “Is the next issue of Miracleman coming soon?”

“Dunno,” he shrugged, sweeping his Sharpie across the inside of my last book. He pushed the books across the table without looking at me, then stood and walked away. Crushed and disappointed, I slunk out of the store.

My fangirl dreams died that day. Most likely a good thing. Neil Gaiman was a man, not a god like Dream, even though he _was_ English.

Later, when I gained a little perspective, I was able to muster some empathy for him. If the store was miserable for me, at least I could stand quietly in line; he had to be nice to everyone. And I heard he was there for hours after I left in that cramped, airless store. While he was distracted and dismissive at my questions, he was also in the midst of a legal battle over Miracleman, and was likely pretty peeved over the whole affair. It’s easy to imagine that the signing was at least as miserable for him as it was for me. From then on, I could be what I imagined a normal fan. I think of him by his last, not his first, name. I’m appreciative of what I like, disappointed in what I don’t, and interested to see what came next.

I think I’ve been to two readings he’s given since then. At neither did I bother with the line.