2009: My Year in Books

Friday, January 1st, 2010

I read 66 books, averaging a book and a half a week, almost 30 fewer than last year. I wasn’t reading less, but had a few doorstops–Infinite Jest and Shadow Country.

A few thoughts:

Best books I read this year: The Story of Edgar Sawtelle by David Wrobleski, The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay by Michael Chabon, Infinite Jest by David Foster Wallace, Olive Kitteridge by Elizabeth Strout, Old Filth by Jane Gardam. These were the whole package–well written, moving, and complex. They made me think and feel.

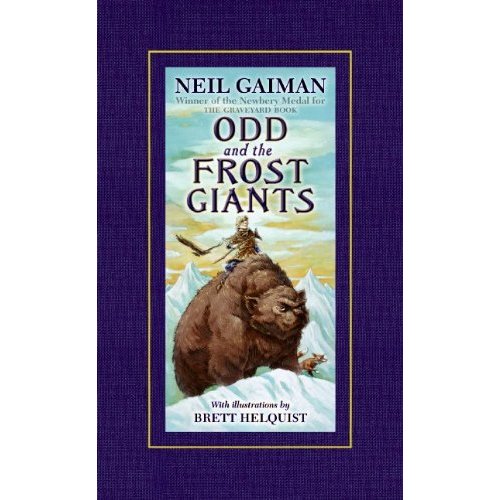

Thumping good reads: Where’s Billie by Judith Yates Borger, Andromeda Klein by Frank Portman, The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo by Stieg Larsson, Beat the Reaper by Josh Bazell, The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society by Mary Ann Shaffer, The Good Thief by Hannah Tinti, The Graveyard Book by Neil Gaiman, Peter and Max by Bill Willingham. These books were devourable and flat-out fun to read, even if they had some decidedly not-fun elements.

D’oh: Fahrenheit 451 and Infinite Jest, for books I liked/loved so much I wish I’d read them earlier in life, so could be re-reading instead of reading for the first time.

Best graphic novels: Alan’s War by Emmanuel Guibert, Scott Pilgrim vs. the Universe by Bryan Lee O’Malley, T-Minus by Jim Ottaviani, Daredevil: Born Again by Frank Miller and Dave Mazzuchelli.

Changed my life: Curly Girl by Lorraine Massey. I gave away my hair-straightening brushes, iron and products. I stopped using shampoo and a blow-dryer. I’ve fully embraced my curly hair, and am happier with my hair than I’ve been in my life.

Weird numbers that probably only I care about: New purchases I read, 32; Library books read, 24; Shelf sitters, 5; Re-reads, 5.

Hopes for the new year, 2010: as usual, read more from my shelf and less from the library and bookstores. I wanted to do a book-a-day challenge to start off the year, but the holidays got the best of me, plus I’m in the middle of Stieg Larsson’s Girl Who Played with Fire, and I’m NOT putting it down. So I may try for a fortnight of books/blogs in February.

I consumed a lot of books and food over Thanksgiving;

I consumed a lot of books and food over Thanksgiving;